APT Octo-Tempest Methods, StripedFly Malware, NetSupport Manager Compromises, and Threat Actors Bypassing MFA

This week: We review APT Octo Tempest/Scatter Spider methods, look into the web of infection from StripedFly malware, discuss how NetSupport Manager is used to compromise entire domains, and review how threat actors leverage phishing toolkits and social engineering to bypass MFA. This and the latest from data leak sites and three new CVEs.

In our latest Cyber Intelligence Brief, Deepwatch ATI looks at new threats and techniques to deliver actionable intelligence for SecOps organizations.

As a leading managed security platform, Deepwatch stands at the forefront of delivering actionable intelligence to keep pace with the ever-evolving threat landscape. Through the Deepwatch Adversary Tactics and Intelligence (ATI) team, we arm your organization with essential knowledge, giving you the power to proactively spot and neutralize risks, amplify your security protocols, and shield your financial stability.

Each week we look at in-house and industry threat intelligence and provide ATI analysis and perspective to shine a light on a spectrum of cyber threats.

Contents

- Octo Tempest/Scattered Spider Methods for Initial Access, Data Exfiltration, and Ransomware Deployment Exposed

- StripedFly Malware Continues to Infect Systems, Estimated 250,000 Systems Infected so Far

- Threat Actor Employs NetSupport Manager to Compromise Entire Domain, Likely Leading to Data Exfiltration

- Threat Actors Increasingly Leverage Phishing Toolkits and Social Engineering to Bypass MFA

- Zero-Day Vulnerability Exploited in Roundcube Webmail Servers (CVE-2023-5631)

- Latest Additions to Data Leak Sites

- CISA Adds 3 CVEs to Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

Octo Tempest/Scattered Spider Methods for Initial Access, Data Exfiltration, and Ransomware Deployment Exposed

Octo Tempest/Scattered Spider/UNC3944 – Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction – Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation – Accommodation and Food Services – Manufacturing – Retail Trade – Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services – Information – Financial and Insurance Services

Threat Analysis

Octo Tempest (0ktapus, Scattered Spider, and UNC3944) is a collective of native English-speaking threat actors known for launching wide-ranging campaigns that prominently feature adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) techniques, social engineering, and SIM swapping capabilities. Octo Tempest was initially seen in early 2022, targeting mobile telecommunications and business process outsourcing organizations. In late 2022 to early 2023, Octo Tempest expanded their targeting to include cable telecommunications, email, and technology organizations. During this period, Octo Tempest started monetizing intrusions by extorting victim organizations for data stolen during their intrusion operations and using physical threats.

In mid-2023, Octo Tempest became an affiliate of ALPHV/BlackCat, and initial victims were extorted for data theft (with no ransomware deployment) using the ALPHV Collections leak site. By June 2023, Octo Tempest started deploying ALPHV/BlackCat ransomware payloads (both Windows and Linux versions) to victims and lately has focused their deployments primarily on VMWare ESXi servers. Octo Tempest progressively broadened the scope of industries targeted for extortion, including natural resources, gaming, hospitality, consumer products, retail, managed service providers, manufacturing, law, technology, and financial services.

In recent campaigns, Microsoft observed Octo Tempest leveraging various TTPs to navigate complex hybrid environments, exfiltrate sensitive data, and encrypt data. Many organizations do not have their tradecraft, such as SMS phishing, SIM swapping, and advanced social engineering techniques, included in their threat models.

For initial access, Octo Tempest predominantly targets technical administrators through sophisticated social engineering attacks, aiming for initial access to accounts. They meticulously research their targets and impersonate victims, manipulating administrators into resetting passwords and multifactor authentication (MFA) methods. The threat actor employs various initial access methods, including manipulating employees to install Remote Monitoring and Management utilities, navigate to fake login portals, or remove their FIDO2 tokens. They also use SIM swapping and call number forwarding, using the victim’s phone number to initiate self-service password resets. Additionally, Octo Tempest purchases employee credentials from criminal underground markets and conducts SMS phishing attacks. In more aggressive tactics, they resort to fear-mongering, using personal information and physical threats to coerce victims into sharing corporate access credentials.

In the reconnaissance and discovery phase, Octo Tempest engages in extensive enumeration and information gathering to secure advanced access within targeted environments, exploiting legitimate channels for subsequent actions. They perform bulk exports of user, group, and device data and probe data and resources in virtual desktop infrastructure and enterprise-hosted resources accessible by a user’s profile. The threat actor conducts broad searches across knowledge repositories to uncover documents pertinent to network architecture, employee onboarding, remote access methods, password policies, and credential vaults.

Octo Tempest extends their reconnaissance to multi-cloud environments, validating access, enumerating databases and storage containers, and planning footholds for future attack phases. They employ tools such as PingCastle, ADRecon, Advanced IP Scanner, Govmomi Go library, and PureStorage FlashArray PowerShell module for Active Directory reconnaissance, network probing, vCenter API enumeration, and storage array enumeration, as well as bulk downloads of user, group, and device information from Azure Active Directory.

For privilege escalation, Octo Tempest leverages their access within mobile telecommunications and business process outsourcing organizations to initiate SIM swaps or set up call number forwarding, performing self-service password resets to gain control of employee accounts. They also manipulate organization help desks into resetting administrator passwords and altering multifactor authentication settings. Octo Tempest also employs advanced social engineering, utilizing stolen password policies, bulk user and role exports, and a deep understanding of target organization procedures to build trust and bypass security measures.

They continually harvest additional credentials using tools like Jercretz and TruffleHog to automate the identification of sensitive information across code repositories. Additional tactics and techniques for access and credential harvesting include modifying access policies, employing open-source tools like Mimikatz, and manipulating Azure VM configurations. Octo Tempest also creates snapshots of virtual domain controller disks to extract critical authentication data and assigns User Access Administrator roles to expand their management scope within compromised environments.

Regarding defense evasion, Octo Tempest strategically compromises security personnel accounts to disable security products and features to maintain stealth throughout their operations. Utilizing compromised accounts, they manipulate EDR and device management technologies to facilitate their malicious activities, deploying RMM software, impairing security products, exfiltrating sensitive files, and deploying malicious payloads.

To conceal their actions, Octo Tempest alters security staff mailbox rules to automatically delete emails from vendors, mitigating the risk of raising suspicion. Additional techniques and tools employed include using the privacy.sexy framework to disable security products, enroll actor-controlled devices into device management software, configure trusted locations in Conditional Access Policies, and replay harvested tokens with satisfied MFA claims, effectively bypassing multi-factor authentication and expanding their access capabilities within the compromised environment.

To establish persistence, Octo Tempest employs publicly available security tools and account manipulation techniques. They target federated identity providers, using tools like AADInternals to federate domains and generate forged SAML tokens with satisfied MFA claims, a technique known as Golden SAML. This tactic is also applied using Okta Org2Org functionality for impersonation. Octo Tempest installs various legitimate RMM tools to maintain endpoint access, utilizes reverse shells across Windows and Linux endpoints, and uniquely compromises VMware ESXi infrastructure to run arbitrary commands on virtual machines. They employ a wide array of open-source tools, such as ScreenConnect, AnyDesk, and TacticalRMM, and leverage Azure virtual machines and third-party tunneling tools like Twingate to enable remote access and bypass network exposure, ensuring persistent and stealthy access within victim environments.

Octo Tempest employs diverse actions on objectives across industries, ranging from cryptocurrency theft and data exfiltration to ransomware deployment. They access and exfiltrate data from various sources, including code repositories, document management systems, and cloud storage, using legitimate management clients for connection and collection. They also use third-party services like FiveTran to exfiltrate data from databases, like SalesForce and ZenDesk, using API connectors, and exfiltrate mailbox PST files and forward mail to external mailboxes.

The threat actor employs anonymous file-hosting services and unique techniques like Azure Data Factory for data movement, aiming to blend in with typical extensive data operations. They also register legitimate Microsoft 365 backup solutions to expedite data exfiltration. Ransomware deployment follows data theft, targeting various endpoints and hypervisors. Octo Tempest directly communicates with victims post-encryption to negotiate or extort ransoms, often causing significant reputational damage through leaked communications.

Octo Tempest primarily operates for financial gain, leveraging their extensive capabilities in social engineering, reconnaissance, credential harvesting, and data exfiltration to compromise and navigate complex hybrid environments. They exhibit a clear objective to infiltrate organizations, steal sensitive data, and deploy ransomware, all while maintaining stealth and persistence within victim networks. Their advanced tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) include manipulating technical administrators for initial access, conducting thorough information gathering across multi-cloud environments, and employing various tools for privilege escalation and defense evasion.

Octo Tempest’s capabilities extend to disabling security products, establishing persistence through account manipulation and using legitimate security tools, and exfiltrating data using anonymous file-hosting services and third-party data movement platforms. While their primary intention appears to be financial gain through data theft, extortion, and ransomware deployment, their activities also indicate a potential for indirect intelligence collection and a desire for notoriety within cybercriminal communities, as evidenced by their direct communications with victims and the leaking of these interactions. Their ability to manipulate, evade, and persist highlights their objectives to conduct prolonged and undetected cyber operations, aiming to profit from their sophisticated and multi-faceted cyber campaigns.

Risk & Impact Assessment

A successful Octo Tempest attack poses severe risks to organizations, leading to substantial material impacts on operations, data, and financial assets. The extensive data exfiltration and manipulation threaten the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive information, risking legal and financial repercussions and potentially losing customer trust. They directly target financial assets through cryptocurrency theft or aggressive extortion tactics, amplifying potential financial losses and materially impacting net sales, revenues, and income from continuing operations. They jeopardize operational continuity as organizations face downtime and resource allocation challenges for mitigation and recovery. At the same time, the reputational damage from public exposure of extortion attempts can lead to a long-term decline in business prospects. Undermining security infrastructure leaves organizations vulnerable to further attacks. The desire for notoriety within cybercriminal communities could escalate future campaign activities, increasing the risk and potential impact on targeted organizations.

Source Material: Microsoft Threat Intelligence, Octo Tempest crosses boundaries to facilitate extortion, encryption, and destruction

StripedFly Malware Continues to Infect Systems, Estimated 250,000 Systems Infected so Far

StripedFly – Cryptomining – Data Theft – SMBv1 exploitation – Industries/All

Threat Analysis

Malware Overview

StripedFly is a complex and multifaceted malware that operates under the guise of a cryptocurrency miner while concealing its true capabilities. The malware includes a framework with modules, including a cryptomining and SMBv1 infection module, similar to EternalBlue, to facilitate infection and expand functionality and a lightweight TOR network client.

Besides the cryptomining and SMBv1 exploitation/infection modules, the malware has additional modules categorized into service and functionality modules. The service modules handle tasks like configuration storage, upgrade/uninstall processes, and a reverse proxy. The functionality modules include a credential harvester, miscellaneous command handler, repeatable tasks, and a recon module. The credential harvester module collects sensitive information from all active users, including website login usernames and passwords, Wi-Fi network names and passwords, and SSH, FTP, and WebDav credentials from popular software clients.

The malware also has an SSH infection module, which attempts to infect Linux hosts by relying on a successful Windows infection using the SMBv1 exploitation module, credential harvesting module, and the SSH protocol, using keys found on the victim’s machine. We describe this process under the Infection Process section.

The miscellaneous command handler module encompasses various commands designed to interact with the victim’s file systems, capture screenshots, retrieve system versions, obtain the active X11 display on Linux, and execute shellcode received from the C2 server. The repeatable task module contains built-in tasks that can be performed once or on a repeatable scheduled basis. The tasks include taking a screenshot, executing a process with a given command line, recording microphone input, and gathering a list of files with specific extensions (this is the only task that works in the Linux version of the malware). This recon module compiles system and network information and transmits it to the C2 server.

A notable aspect of StripedFly is its connection to the ThunderCrypt ransomware. An earlier malware version shared the same underlying codebase and communicated with the same C2 server, highlighting their intertwined nature. ThunderCrypt ransomware used the file listing component of the repeatable task module as an integral part of its ransom encryption process. However, ThunderCrypt lacks the SMBv1 infection module found in StripedFly.

StripedFly uses the Bitbucket repository to minimize its initial footprint, which hosts an encrypted and compressed custom binary archive disguised as firmware binaries. This repository also contains binaries to update the malware if the command and control (C2) server is unresponsive. The Bitbucket repository was created on 21 June 2018 and includes five binary files: delta.dat, delta.img, ota.dat, ota.img, and system.img, hosted under the Downloads folder.

The system.img file is the payload for Windows systems. Bitbucket includes a download counter feature that reflects the number of downloads since the last file update. Kaspersky says that the download counter for this file accurately reflects the number of new infections since its last update. Kaspersky stated that in June 2022, the download counter showed 160,000 downloads, with the last update on 24 February 2022. The Adversary Tactics and Intelligence team discovered that as of 27 October 2023, the download counter read almost 87,000 since the last update on 22 April 2023.

While the malware primarily receives updates from its C2 server, if the C2 server is unresponsive, it resorts to downloading updates from the repository. Two binaries, ota.dat (Windows) and delta.dat (Linux), serve as tools for the malware to check for the availability of new updates.

As of 27 October, the repositories download counter for ota.dat shows over 1.2 million downloads. Kaspersky stated that at the time of writing, there were eight updates for Windows systems, so each infected system would, we assume, download files each time it was updated. Additionally, delta.dat has almost 19,000 downloads. Kaspersky states that delta.dat, besides serving as an update mechanism for Linux systems, is also the initial infection payload for Linux hosts compromised via SSH by the Windows version. So it’s unclear how many downloads for delta.dat are new infections or updates.

Analyst Note: It is unclear whether the eight Windows updates occurred prior to or between June 2022 and April 2023. If we assume the numbers provided by Kaspersky are the total number of downloads and they represent the number of infected devices, and that there were no downloads from the repository that Kaspersky did not include. We estimate with moderate to high confidence that the number of infected systems is around 250,000 (160,000 downloads of system.img in June 2022 and 87,000 downloads of system.img on 27 October 2023). However, there is a possibility that this is not the total number of updates. Kaspersky may not have captured all the downloads for each update or additional variants employing other methods to download system.img. Therefore, the total number of downloads would likely exceed the estimated 250,000.

Infection Process

It is unclear how the threat actors gained initial access, but to infect Windows systems, the malware utilizes the SMBv1 infection module, a custom version of the EternalBlue exploit, to execute shellcode within the Windows Kernel. The shellcode then injects additional shellcode into the WININIT.EXE process, which downloads binary files from the bitbucket[.]org repository and executes PowerShell scripts. Once the payload is deployed, the malware will propagate to Linux Hosts via the SSH exploitation module and employ various persistence mechanisms. Once the credential harvester module completes its tasks, the malware will filter the results for SSH keys and credentials and, if any are found, retrieve delta.dat and delta.img either from the cache or directly from bitbucket[.]org repository. Then, it attempts to connect to the remote SSH server. If the connection is successful and the remote system is supported, the malware uploads its binary to the /tmp folder and executes it.

The persistence mechanisms involve adapting its behavior based on the system’s configuration and the privileges it can access. On systems where PowerShell is available, the malware’s tactics vary. With administrative rights, it leverages PowerShell to create two task scheduler entries, each with unique triggers and GUID-like names, to execute a PowerShell loader script. Without administrative privileges, it places a PowerShell script loader, padded with thousands of spaces at both ends, in the Windows registry key, HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Applets. This script is run at startup via a PowerShell command stored in another Windows registry key, HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. In administrative and non-administrative scenarios, the payload itself is stored in yet another registry key, Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Shell, which is also obfuscated with Base64 encoding and surrounded by hundreds of spaces and is executed when the PowerShell mentioned above loader script is executed.

In the unlikely event that PowerShell is unavailable, StripedFly creates a hidden MZ-PE loader file with a randomized name in the %APPDATA% directory, embedding a copy of system.img. This loader is then registered within the Windows registry key HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run for persistence. On Linux systems, the malware disguises itself as (sd-pam), employing various methods for persistence, ranging from system or user systemd services, autostarted .desktop files, to additional lines in /etc/rc*, profile, bashrc, or inittab files. The malware’s executable is stored in the /tmp directory under a random name, ensuring its operation across different platforms and configurations.

Threat Actor Intentions, Objectives, and Capabilities

The threat actors behind StripedFly exhibit a multifaceted set of intentions, objectives, and capabilities, orchestrating a sophisticated cyber operation. Their objectives are clearly outlined by deploying a complex malware framework, aiming for unauthorized access, data exfiltration, system interaction, and persistent infiltration across Windows and Linux platforms. Using an SMBv1 infection module, credential harvesting, and various system interaction and surveillance modules, alongside advanced evasion and persistence techniques, showcases their technical prowess and adaptability.

In terms of intentions, the actors appear to be primarily driven by intelligence collection, with a secondary intention of financial gain, as evidenced by including a cryptomining module and extensive data collection capabilities. The threat actors have demonstrated significant resourcefulness and technical sophistication, ensuring the resilience and effectiveness of their operation through redundant update mechanisms and a broad targeting scope.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The StripedFly malware presents substantial risks and potential impacts to organizations, posing threats to the confidentiality of systems, data, and operations. The malware’s extensive capabilities for unauthorized access, data exfiltration, and system interaction place sensitive information at risk of disclosure and compromise, threatening critical data. Operations could face severe disruptions due to the malware’s network propagation and potential for executing disruptive commands, necessitating significant resource diversion for mitigation and recovery efforts.

The financial ramifications are considerable, with potential direct and indirect losses stemming from operational downtime, remediation costs, legal liabilities, and reputational damage. These financial ramifications could manifest in material impacts on net sales, revenues, and income from continuing operations, particularly if the organization cannot swiftly and effectively respond to the infection. The cumulative effect of these factors underscores the need for robust preventative measures and incident response plans to mitigate the risks and potential impacts associated with StripedFly, safeguarding the organization’s assets, data, and operational continuity.

Source Material: SecureList/Kaspersky, StripedFly: Perennially flying under the radar

Threat Actor Employs NetSupport Manager to Compromise Entire Domain, Likely Leading to Data Exfiltration

NetSupport Manager – Phishing – Reverse SSH Tunneling – Domain Compromise – Industries/All

Threat Analysis

In January 2023, a threat actor infiltrated a DFIR Report honeypot employing the NetSupport Manager remote access tool, resulting in a full domain compromise. The DFIR Report’s honeypots are controlled simulated environments, likely aiming to appear like a real organization. However, the blog post does not disclose the activities employed against a real organization. This intrusion began with a malicious email attachment, a zip file containing a harmful JavaScript file. Extracting and running the JavaScript file fetched and executed an obfuscated PowerShell script directly in memory. This PowerShell script was crucial in deploying the NetSupport remote access tool onto the system, ensuring it was not running in a sandbox environment, and establishing persistent access through registry run keys.

Five days later, the adversary initiated preliminary reconnaissance activities, utilizing a variety of Windows utilities such as whoami, net, and systeminfo. They attempted to reactivate a disabled domain admin account, though it seemed they were not successful in this endeavor. However, the threat actor made minor mistakes, either with typos or in command functionality.

Subsequently, the adversary installed an OpenSSH server on the initial compromised host to maintain persistent access to the machine and network. To connect to this OpenSSH server, they established a reverse SSH tunnel from the compromised host to their server hosted on a Virtual Private Server (VPS) provider.

Leveraging the reverse SSH tunnel to route connections through the compromised host, the adversary established a connection to the domain controller. They utilized Impacket’s atexec.py to execute various discovery commands, aiming to identify privileged groups and domain-joined computers.

Eight hours later, the adversary altered firewall settings on a remote server and used Impacket’s wmiexec.py for additional lateral movement. They transferred cab files to remote hosts using SMB, expanded, and executed them using wmiexec.py commands. These executed files were also instances of NetSupport Manager, configured to communicate with a new command and control server. Following this, the adversary set up a scheduled task for persistence on these remote hosts and executed a few more discovery commands before halting their activity.

The adversary resumed their operations the following day, deploying NetSupport Manager on a domain controller and subsequently dumping the NTDS.dit database. They compressed the files using 7-zip. While The DFIR Report did not observe specific exfiltration activities, they assessed with medium confidence that this archive was exfiltrated over the network via one of the established command and control channels.

Less than an hour later, the adversary targeted another domain controller, again dumping the NTDS.dit database, and deploying Pingcastle, an active directory auditing tool. Concurrently, they utilized NetSupport to access a backup server, create a new account, and add it to the local Administrators and Remote Desktop groups. They then accessed the system using RDP, routing the connection through the compromised host.

Upon gaining access, they deployed Netscan and a keygen, checked the status of Microsoft Defender, disabled it, and dumped LSASS on both the domain controller and a backup server. Following this, they issued a PowerShell command to search and dump Windows event ID 4624 logon events, which were then compressed using 7-zip and likely exfiltrated. The adversary also explored file shares on the domain controller, accessing numerous sensitive documents. They transferred Netscan to the domain controller, executed it, issued additional discovery commands via WMI, and performed cleanup activities, including terminating running tasks like Netscan and the SSH proxy.

The adversary’s final observed actions involved deploying two Nim binaries on a domain controller, attempting to create a backdoor user, and elevate their permissions to admin level. However, The DFIR Report did not observe the creation of a backdoor account after execution. The DFIR Report’s testing revealed that the tool failed to function, returning an error. Following this, the adversary’s hands-on activity ceased, and they were removed from the network.

The threat actor demonstrated a clear intention toward intelligence collection or financial gain. Their objectives centered on gaining unauthorized access to the network, accessing and collecting sensitive information, exfiltrating this data, and ensuring persistent access to the compromised systems. While there is a possibility of financial gain through the sale of accessed data or potential extortion, the lack of overt disruptive activities makes sabotage or hacktivism almost uncertain.

Regarding capabilities, the threat actors exhibited basic and advanced skills, employing common phishing methods and publicly available tools for initial access and data collection while demonstrating advanced network maneuvering and lateral movement capabilities. Their knowledge of network systems, security evasion techniques, and exploitation tools underscores their competence in conducting cyber attacks despite making some operational mistakes during the discovery phase. Overall, the threat actors’ actions reflect a well-coordinated effort to infiltrate the network, gather data, and maintain access.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The successful attack poses substantial risks and impacts across various facets of an organization. The most pronounced risk stems from the loss of confidentiality, as the actors demonstrated a keen interest in accessing and likely exfiltrating sensitive data, which could lead to significant operational disruptions due to necessary investigative and remedial actions, as well as a tangible loss of valuable data assets. A successful compromise will likely erode customer trust, resulting in a potential decline in business, adversely affecting net sales and revenues, and incurring additional costs related to legal actions, regulatory fines, and remediation efforts, thereby diminishing income from continuing operations. The DFIR Report removed the threat actor from the environment before they could deny service or modify, encrypt, wipe, or destroy any data. Therefore, we cannot assess the risks and impact on the availability or integrity of systems and data.

Source Material: The DFIR Report, NetSupport Intrusion Results in Domain Compromise

Threat Actors Increasingly Leverage Phishing Toolkits and Social Engineering to Bypass MFA

MFA Bypass – Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM) – Phishing-as-a-Service – EvilProxy, Evilginx2, and W3LL Phishing Kits – Industries/All

Threat Analysis

Kroll has observed a noticeable escalation in adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) phishing and business email compromise (BEC) attacks, with 90% of investigated organizations having Multifactor Authentication (MFA) implemented at the time of unauthorized access. Threat actors bypass MFA susceptible to phishing, push bombing, or SS7 and SIM swap attacks by leveraging sophisticated phishing-as-a-service toolkits and social engineering tactics to compromise passwords and MFA tokens. These methods are particularly prevalent against popular cloud services such as Microsoft 365.

These phishing-as-a-service toolkits, readily available on dark web forums or as subscription services, enable threat actors to intercept credentials, MFA codes, cookies, and session tokens through targeted phishing attacks. Once a user is authenticated and a session cookie is created, threat actors can steal this cookie, nullifying the need for credentials or an MFA token to maintain access to the victim’s account. Traditional MFA factors, including challenge/response and app-based codes, are susceptible to this interception and replay.

Notable toolkits facilitating these attacks include EvilProxy, Evilginx2, and W3LL. EvilProxy, for instance, creates phishing links that mimic well-known services to harvest credentials, tokens, and session cookies. A specific campaign utilized EvilProxy to target C-suite employees across various sectors, employing an open redirect technique against the legitimate “indeed.com” domain to lead victims to a deceptive Microsoft 365 login page. This deception captured credentials and session cookies upon the victim’s authentication to the legitimate service. Evilginx2 and W3LL are other prevalent phishing toolkits, with W3LL capturing credentials of over 56,000 Microsoft 365 accounts in September. These toolkits can emulate login pages for prominent platforms, enhancing their deception capabilities.

MFA fatigue, another technique employed by threat actors, involves spamming the victim with push notifications until they approve an authentication request. This technique relies on the victim having a “simple approval” method enabled, where approving the push notification is the only thing required to complete the authentication. Employees using the “simple approval” method may not know which authentication session they are approving. To employ MFA fatigue, threat actors typically have to gain access to credentials first, either through previous compromises or purchases on the dark web.

Scattered Spider has been observed utilizing the MFA fatigue technique, achieving initial access predominantly through targeted social engineering, including phone calls and SMS messages. They have also been known to directly contact an organization’s help desk to manipulate victims into resetting user passwords and altering MFA tokens/factors, facilitating unauthorized access.

Risk & Impact Assessment

Successful MFA bypass attacks employing tactics such as MFA fatigue and adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) phishing attacks pose significant risks and impacts to organizations, potentially leading to severe reputation damage, financial losses, operational disruptions, intellectual property theft, and data breaches. The erosion of trust among customers, partners, and stakeholders can result in a tangible decrease in sales and revenues, as trust is a critical component in customer relationships, especially in sectors like banking, financial services, and healthcare.

Direct financial losses may stem from fraudulent transactions and unauthorized access to financial accounts, alongside indirect costs related to incident response, legal fees, and potential regulatory fines. Operational disruptions can lead to downtime and loss of productivity, with prolonged impacts if critical systems or data are compromised. The theft of intellectual property and sensitive information can erode competitive advantages, stifle innovation, and lead to long-term market position losses. Furthermore, data breaches and privacy violations can result in legal and regulatory consequences, further damaging the organization’s financial stability and prospects. Cumulatively, these factors can materially impact net sales, revenues, and income from continuing operations, underscoring the imperative for robust security measures and vigilant threat monitoring.

Source Material: Kroll, Rise in MFA Bypass Leads to Account Compromise

Zero-Day Vulnerability Exploited in Roundcube Webmail Servers (CVE-2023-5631)

Roundcube Webmail Server CVE-2023-5631 – Winter Vivern – Phishing – Data Exfiltration – Public Administration – Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services

Threat Analysis

On 11 October, ESET observed Winter Vivern, a cyberespionage group first identified in 2021 and potentially active since 2020, exploiting a JavaScript injection vulnerability in Roundcube Webmail servers. The group has been observed historically targeting Zimbra and Roundcube email servers belonging to governmental entities across Europe and Central Asia since at least 2022. Winter Vivern employs various tactics, including malicious documents, phishing websites, and a custom PowerShell backdoor in their campaigns.

Notably, ESET observed that the JavaScript injection was effective on a fully patched Roundcube instance. ESET discovered that this was a zero-day XSS vulnerability affecting a server-side script, which fails to properly sanitize malicious SVG documents before being added to the HTML page interpreted by a Roundcube user. ESET reported the vulnerability to Roundcube on 12 October, and Roundcube issued a patch on 14 October. The vulnerability, now tracked as CVE-2023-5631, affects Roundcube versions before 1.4.15, 1.5.x before 1.5.5, and 1.6.x before 1.6.4. Threat actors can exploit this vulnerability by sending an HTML email to the target with a crafted SVG document.

Winter Vivren exploited this vulnerability by inserting a malicious SVG tag at the end of their emails. This SVG tag contains a base64-encoded payload that, when decoded, executes arbitrary JavaScript code in the victim’s browser. Winter Vivren’s email, observed by ESET, originated from the address team.managment@outlook[.]com with the subject “Get started in your Outlook.” This arbitrary JavaScript code, once executed, contacts a command and control (C&C) server, recsecas[.]com, to fetch a simple JavaScript loader named checkupdate.js. The final JavaScript payload lists folders and emails in the compromised Roundcube account and exfiltrates email messages to the C&C server via an HTTP request to https://recsecas[.]com/controlserver/saveMessage.

Winter Vivern’s ability to exploit a previously unknown vulnerability indicates an advancement in their technical skills and resources. Previously, they used known vulnerabilities in Roundcube and Zimbra, with publicly available proofs of concept. Their latest campaign demonstrates clear intentions for intelligence collection, aiming to gather sensitive information that could provide political, economic, or strategic advantages. Their objectives center on gaining unauthorized access to sensitive data, collecting intelligence, and exfiltrating this information for analysis. Overall, Winter Vivern is a formidable threat actor with clear objectives and robust capabilities.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The exploitation of CVE-2023-5631 by threat actors poses severe and multifaceted risks to organizations utilizing vulnerable Roundcube Webmail servers, likely resulting in substantial material impacts across various domains. Operationally, organizations may experience significant disruptions and resource reallocations, potentially leading to downtime and delayed projects. The unauthorized access and likely exfiltration of sensitive data, including internal communications, directly compromise data confidentiality and integrity, resulting in losing competitive advantage and stakeholder trust.

Financially, victim organizations face immediate remediation costs, potential loss of revenue due to operational disruptions and reputational damage, and legal and regulatory penalties stemming from data protection violations. Strategically, the theft of sensitive information can erode the organization’s competitive standing. Cumulatively, these impacts pose a substantial threat to the organization’s net sales, revenues, and income from continuing operations, underscoring the critical need for immediate action to mitigate risks and safeguard organizational assets and operations.

Source Material: ESET Research, Winter Vivern exploits zero-day vulnerability in Roundcube Webmail servers

Latest Additions to Data Leak Sites

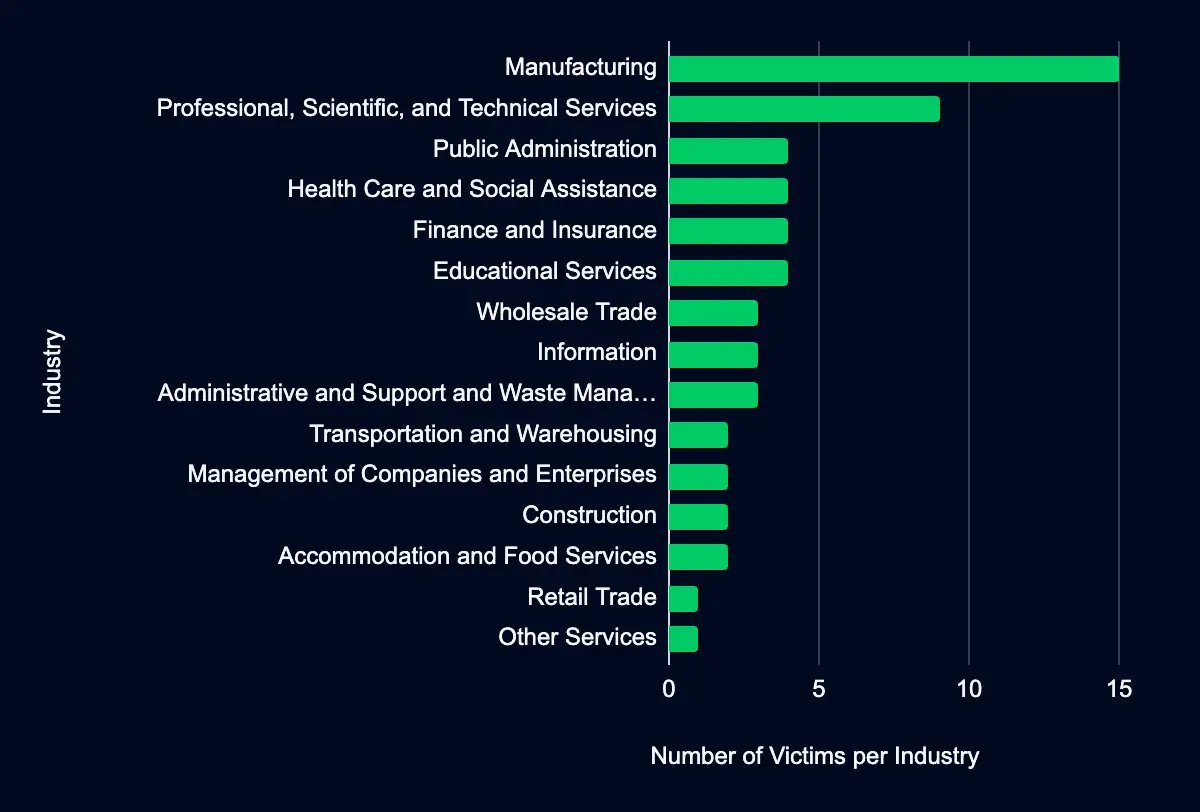

Manufacturing – Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services – Public Administration – Health Care and Social Assistance – Finance and Insurance

In the past week, monitored data extortion and ransomware threat groups added 59 victims to their leak sites. Of those listed, 39 are based in the USA. Manufacturing was the most affected industry, with 15 victims. The Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services industry follows with nine victims, and four victims each in Public Administration, Health Care and Social Assistance, and Finance and Insurance. This information represents victims whom cybercriminals may have successfully compromised but opted not to negotiate or pay a ransom. However, we cannot confirm the validity of the cybercriminals’ claims.

CISA Adds 3 CVEs to Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

F5 BIG-IP Configuration Utility CVE-2023-46748 & CVE-2023-46747 – Roundcube Webmail CVE-2023-5631

In the past week, CISA added three CVEs to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog, impacting products from F5 and Roundcube. These vulnerabilities can have severe consequences, including authentication bypass, SQL injection, or run malicious JavaScript code. It is currently unknown if these vulnerabilities are linked to any ransomware campaigns. Dive into this report to understand the risks and CISA’s recommended mitigation timeline. Ensure your systems are safeguarded.

Recommendations

ATI recommends mitigative action occur according to the mitigation “Due Date” recommended by CISA.

| CVE ID | Vendor/Project | Product | Description | CISA Due Date | Known to be Used in Ransomware Campaigns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2023-46748 | F5 | BIG-IP Configuration Utility | F5 BIG-IP Configuration utility contains an SQL injection vulnerability that may allow an authenticated attacker with network access through the BIG-IP management port and/or self IP addresses to execute system commands. This vulnerability can be used in conjunction with CVE-2023-46747. | 2023-11-21 | Unknown |

| CVE-2023-46747 | F5 | BIG-IP Configuration Utility | F5 BIG-IP Configuration utility contains an authentication bypass using an alternate path or channel vulnerability due to undisclosed requests that may allow an unauthenticated attacker with network access to the BIG-IP system through the management port and/or self IP addresses to execute system commands. This vulnerability can be used in conjunction with CVE-2023-46748. | 2023-11-21 | Unknown |

| CVE-2023-5631 | Roundcube | Webmail | Roundcube Webmail contains a persistent cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability that allows a remote attacker to run malicious JavaScript code. | 2023-11-16 | Unknown |

Let’s Secure Your Organization’s Future Together

At Deepwatch, we are committed to helping organizations like yours navigate the intricate world of cyber threats. Our cybersecurity solutions are designed to stay ahead of the curve, providing you with the proactive defenses needed to protect your organization from these threats.

Our team of cybersecurity professionals is ready to evaluate your systems, provide actionable insights, and implement robust security measures tailored to your needs.

Don’t wait for a cyber threat to disrupt your operations. Contact us today and take the first step towards a more secure future for your organization. Together, we can outsmart the threats and secure your networks.

What We Mean When We Say

Estimates of Likelihood

We use probabilistic language to reflect the Intel Team’s estimates of the likelihood of developments or events because analytical judgments are not certain. Terms like “probably,” “likely,” “very likely,” and “almost certainly” denote a higher than even chance. The terms “unlikely” and “remote” imply that an event has a lower than even chance of occurring; they do not imply that it will not. Terms like “might” reflect situations where we are unable to assess the likelihood, usually due to a lack of relevant information, which is sketchy or fragmented. Terms like “we can’t dismiss,” “we can’t rule out,” and “we can’t discount” refer to an unlikely, improbable, or distant event with significant consequences.

Confidence in Assessments

Our assessments and projections are based on data that varies in scope, quality, and source. As a result, we assign our assessments high, moderate, or low levels of confidence, as follows:

High confidence indicates that our decisions are based on reliable information and/or that the nature of the problem allows us to make a sound decision. However, a “high confidence” judgment is not a fact or a guarantee, and it still carries the risk of being incorrect.

Moderate confidence denotes that the information is credible and plausible, but not of high enough quality or sufficiently corroborated to warrant a higher level of assurance.

Low confidence indicates that the information’s credibility and/or plausibility are in doubt, that the information is too fragmented or poorly corroborated to make solid analytic inferences, or that we have serious concerns or problems with the sources.

Share