TicTacToe Dropper Is No Game, No Malware Needed for Access to Government Victim, and Tycoon Group Offers New Phishing-as-a-Service

This week: a new malware dropper was discovered, threat actors gain access to government through former employee, Tycoon Group starts Phishing-as-a-Service, this plus nearly 100 ransomware victims despite Lockbit takedown.

In our latest Cyber Intelligence Brief, Deepwatch ATI looks at new threats and techniques to deliver actionable intelligence for SecOps organizations.

Each week we look at in-house and industry threat intelligence and provide ATI analysis and perspective to shine a light on a spectrum of cyber threats.

Contents

- New Malware Dropper Family, Delivering Various Payloads, Discovered

- Cyber Attack With No Malware, Compromised Account Used to Access and Exfiltrate Sensitive Data

- New Phishing-as-a-Service Platform Discovered

- Latest Additions to Data Leak Sites

- CISA Adds 2 CVEs to Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

New Malware Dropper Family, Delivering Various Payloads, Discovered

Malware – Phishing – Multi-stage Infection Chain – Dropper – TicTacToe Dropper – SmartAssembly – DeepSea Obfuscator – Obfuscation Tool – Industries/All

Threat Analysis

Throughout 2023, a family of malware droppers, dubbed TicTacToe Dropper, that share common characteristics, was used to deliver various final-stage payloads, such as Leonem, AgentTesla, SnakeLogger, RemLoader, Sabsik, LokiBot, Taskun, Androm, Upatre, and Remcos. Variants of the dropper were usually delivered through phishing email campaigns with an attached .iso file. These ISO files contained an executable, which initiated a multiple-stage infection chain, employing multiple nested DLL files, which were extracted at runtime and loaded directly into memory.

Due to the multiple final payloads delivered, multiple threat actors likely employ the TicTacToe dropper, suggesting it’s being sold as a Dropper-as-a-Service. In early 2023, initial versions used a specific Polish string embedded within the code, ‘Kolko_i_krzyzyk’ (which translates to ‘TicTacToe’ in English). As the year progressed, new campaigns used droppers with different, unique strings, such as ‘MatrixEqualityTestDetail,’ ‘QuanLyCafe,’ ‘Pizza_Project,’ ‘Kakurasu,’ ‘BanHang_1’, and ‘ChiuMartSAIS.’ Despite these droppers being part of the same campaign and sharing a common unique identifier, they delivered various final payloads.

Three variants of the TicTacToe dropper family, ALco.exe, IxOQ.exe, and oJXU.exe, were analyzed. All analyzed variants share the following characteristics:

- Employ a multi-stage nested DLL payload infection chain.

- All dropper payloads are .NET executables/libraries.

- One or more of the payloads are obfuscated using SmartAssembly.

- The DLL files are nested and used to unpack obfuscated payloads.

- All payloads, including the final payload, were loaded reflectively.

- Most initial .NET payloads had internal names with a combination of 3 to 8 letters in varying cases.

- Many samples shared common strings (e.g., Kolko_i_krzyzyk, MatrixEqualityTestDetail, Kakurasu, etc.) for the month they were delivered.

- Some of the variants try to create a copy of themself.

ALco.exe Variant

ALco.exe is a 32-bit executable developed in the .NET programming language. Upon execution, the dropper extracts and loads a .NET PE DLL (Stage 2) directly into its current process (directly into memory without being written to disk) using a runtime assembly object.

The extracted Stage 2 DLL was named ‘Hadval.dll’ in the OriginalFileName field in the file’s version information. This DLL was obfuscated with version 4.1 of the DeepSea software, which differs from the obfuscation method used in the initial executable, resulting in unreadable function names and clear indicators of code flow obfuscation. This Stage 2 DLL (Hadval.dll) extracts a gzip blob containing another 32-bit PE DLL file (Stage 3).

The Stage 3 payload has the internal filename ‘cruiser.dll,’ which was obfuscated by SmartAssembly. The cruiser.dll file has a function that creates a copy of the executable in the temp folder. The code from the Stage 3 DLL (cruiser.dll) extracts, reflectively loads, and executes the Stage 4 payload from a resource in the primary payload.

The Stage 4 payload is another .NET PE DLL with the internal name ‘Farinell2.dll,’ obfuscated with a custom obfuscator. This Stage 4 payload then de-obfuscates, reflectively loads, and executes the final payload (Stage 5). Multiple variants of this dropper deploy various final payloads, such as Lokibot, to steal credentials from browsers and software in the victim machine to Remcos RAT for remote access.

A high-level overview of the infection chain:

ALco.exe > Hadval.dll > cruiser.dll > Farinell2.dll > Final payload

IxOQ.exe Variant

IxOQ.exe employs a 4-stage infection chain vs. the 5 that the ‘ALco.exe’ variant employed. This executable was also a 32-bit .NET executable. This executable was not obfuscated but shares similarities with the ‘ALco.exe’ variant, e.g., later-stage obfuscated payloads embedded as object resources. This variant also contained a 32-bit .NET PE DLL (Stage 2).

This stage 2 payload had the internal name of ‘Pendulum.dll.’ When executed, This DLL will extract the Stage 3 payload that shares the same file name (cruiser.dll) as the Stage 3 payload DLL of the ‘ALco.exe’ variant and uses the same loading process. The Stage 3 payload (cruiser.dll) extracts the Stage 4 payload from a resource in the primary payload (IxOQ.exe). This and the ‘ALco.exe’ variant present similar obfuscated image objects, which are visually identical between samples.

The extracted final payload was found to be another 32-bit .NET PE DLL with the internal name ‘Discompard.dll.’ The code from this payload was also loaded reflectively, as in previous stage payloads. Multiple antivirus engines detected this final payload (Discompard.dll) as the Zusy Banking Trojan (TinyBanker or Tinba) or Leonem.

A high-level overview of the infection chain:

IxOQ.exe > Pendulum.dll > cruiser.dll > Discompard.dll (final payload)

oJXU.exe Variant

The oJXU.exe is an earlier variant that used the Polish string, ‘Kolko_i_krzyzyk’ (TicTacToe in English). This variant is also a 32-bit .NET executable. It employs an identical technique to load code stored in the resource object of the file. When the resource object was checked, it was very similar to the resource object used by the IxOQ.exe variant.

The Stage 2 payload has the internal name ‘Pendulum.dll,’ and the Stage 3 payload has the name ‘cruiser.dll.’ On execution, the Stage 3 payload extracts the Stage 4 payload from an image object. Again, the visual aspects of this embedded image object match those of ALco.exe and IxOQ.exe. The final payload was AgentTesla.

A high-level overview of the infection chain:

oJXU.exe > Pendulum.dll > cruiser.dll > AgentTesla

Since each variant drops a different final payload, each would have a different hash. As a result, while hash-based detections can effectively mitigate static threats, this dropper family requires a behavior-based approach to detect new campaigns. The multi-stage payload extraction and in-memory execution behaviors exhibited by this dropper are abnormal compared to normal application execution; Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions should be able to detect and block this behavior.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The TicTacToe Dropper represents a significant risk to organizations due to its multifaceted nature and the variety of payloads it can deliver. The risk associated with this malware dropper stems from its multi-stage infection chain and known distribution through phishing email campaigns, leading to unauthorized access, malware deployment, and the potential for data exfiltration and further malicious activities. The likelihood of the TicTacToe Dropper impacting an organization, while difficult to assess due to the lack of intelligence on the success, scope, and extent of the phishing campaigns, is likely, given the dropper’s multi-stage infection chain, designed evasion techniques, and the observed continuous development to bypass security measures.

A cyberattack facilitated by the TicTacToe Dropper could profoundly impact an organization, especially if it successfully deployed additional malware. Financially, it could lead to substantial losses due to operational downtime, data recovery efforts, legal fees, and potential fines for compliance violations. The reputational damage could erode stakeholder trust, affecting customer relationships and leading to a loss of business. Furthermore, the theft or compromise of sensitive data could have long-term implications on competitive advantage, exposing the organization to further targeted attacks. The cumulative effect of these impacts underscores the need for organizations to prioritize this threat.

Source Material: Fortinet, TicTacToe Dropper

Cyber Attack With No Malware, Compromised Account Used to Access and Exfiltrate Sensitive Data

Valid Account Abuse – Privilege Escalation – Data Exfiltration – VPN Abuse – LDAP Query – Directory Enumeration – Public Administration

Threat Analysis

An unidentified threat actor gained initial access by utilizing the compromised account of a former employee with administrative privileges (USER 1), which did not have multifactor authentication enabled, to conduct reconnaissance and discovery activities. Unfortunately, this account was not disabled immediately following the employee’s departure. Collected logs revealed the threat actor employed an unknown virtual machine (VM) to connect to the victim’s on-premises environment via the victim organization’s VPN, intending to blend in with legitimate traffic to evade detection.

- Due to USER 1 credentials appearing in publicly available channels containing leaked account information, the threat actor likely obtained this account’s credentials in a separate data breach.

- USER 1 account had access to a virtualized SharePoint server and the former employee’s virtualized workstation.

Using the access available to USER 1, the threat actor likely obtained a global domain administrator account (USER 2) from the virtualized SharePoint server because USER 2 credentials were stored locally on this server.

- The threat actor authenticated to multiple services via the USER 1 and USER 2 accounts through the VM connection.

- The USER 2 account granted administrative privileges to the on-premises AD and Azure AD environments.

Through the threat actor’s VM connection, they executed four (4) LDAP queries of the on-premises AD. Based on the query output format, the threat actor likely used the open-source tool AdFind.exe. CISA and MS-ISAC assess the threat actor executed the LDAP queries to collect user, host, and trust relationship information. It is also believed the LDAP queries generated the text files (ad_users.txt, ad_computers.txt, and trustdmp.txt) the threat actor posted for sale on a dark web brokerage site.

- The LDAP queries collected names and metadata of users and hosts in the domain, trust information in the domain, and Domain Administrators and Service Principals in the domain.

Through the VM, the threat actor was observed authenticating to 16 services on the victim organization’s network from the USER 1 and USER 2 administrative accounts. In all instances, the threat actor authenticated to the Common Internet File Service (CIFS) on various endpoints, which provided shared access to files and printers between machines on the network. This was likely used for file, folder, and directory discovery and assessed to be executed in an automated manner. Additionally, the threat actor used compromised accounts to interact with a remote network share using the Server Message Block protocol.

- The threat actor authenticated to four services using USER 1, presumably for network and service discovery.

- The threat actor authenticated to twelve services using USER 2.

High-level overview of the intrusion chain:

- The threat actor likely gathered valid account credentials in a data breach where account information appeared in publicly available channels.

- The actor gained initial access through the compromised valid account (USER 1) of a former employee with administrative privileges.

- The actor connected a VM via the victim’s VPN to blend in with legitimate traffic to evade detection.

- The actor likely obtained a second administrator account (USER 2) credentials from a virtualized SharePoint server, where they were locally stored using the USER 1 account.

- Through the VM connection, the actor executed LDAP queries of the AD to collect user and host information and trust relationship information.

- The actor used the compromised USER 1 account to authenticate to four (4) services, presumably for network and service discovery.

- The actor authenticated to 12 services using the USER 2 account (Global Domain Administrator account). The actor also authenticated to the Common Internet File Service (CIFS) on various endpoints, likely for file, folder, and directory discovery.

- Using the Server Message Block protocol, the actor used compromised accounts to interact with a remote network share.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The abuse of valid accounts, particularly those with administrative privileges that lack multifactor authentication, represents a substantial risk to organizations across various sectors. This type of cyber attack underscores the critical vulnerabilities associated with inadequate account security measures and the failure to promptly deactivate accounts post-employment. The risk is primarily characterized by the ease with which threat actors can gain initial access and perform reconnaissance within an organization’s network undetected. Using techniques like connecting to the victim’s VPN through a virtual machine to mimic legitimate traffic further complicates detection efforts and increases the likelihood of significant impact.

Organizations targeted by such attacks could face dire consequences. Financially, the repercussions extend beyond immediate remediation costs, potentially incurring significant expenses related to legal liabilities and compliance penalties. The operational impact is equally grave, with potential disruptions to critical services, loss of productivity, and the costly diversion of resources towards incident response and recovery. The reputational impact is perhaps more damaging in the long term; breaches of this nature can severely erode stakeholder trust, leading to a loss of business and diminished public confidence. The theft or unauthorized access to sensitive data facilitated by such breaches poses a persistent threat with far-reaching implications for an organization’s competitive edge and security posture. The risk of further targeted attacks and the potential for espionage activities underscore the strategic importance of robust cybersecurity practices.

Source Material: CISA, Threat Actor Leverages Compromised Account of Former Employee to Access State Government Organization

New Phishing-as-a-Service Platform Discovered

Phishing-as-a-Service – Phishing – Credential Theft – WebSocket Communication – Tycoon Group – Two-Factor Authentication Bypass – Active Directory Federation Services Cookies – Industries/All

Threat Analysis

The Tycoon Group Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS) platform provides an admin panel accessible to subscribers, enabling them to log in, generate and oversee campaigns, and manage stolen credentials, including usernames, passwords, and session cookies. Depending on their subscription plan, subscribers may access the panel for a limited duration. Users can generate new campaigns within the settings section, selecting the desired phishing theme and toggling various PaaS features on or off. The service also allows subscribers to forward phishing results to their Telegram account. Also displayed within the admin panel are metrics such as Bot Blocked, Total Visits, Valid Logins, Invalid Logins, and the count of Single Sign-On logins.

Within the stolen credentials table, each row features a “Get Cookies” button that enables threat actors to download a JavaScript file that allows them to set stolen cookies onto the browser, which can be used alongside the stolen password for unauthorized access to the victim’s account.

Leveraging scanned sessions in Urlscan.io containing artifacts and filenames related to Tycoon Group’s PaaS offering, scanned session data shows the earliest Tycoon Group’s phishing page submission occurred on 25 August 2023, which may be around the time frame Tycoon Group introduced this service.

On 22 October, a URLScan.io scan submission shows the use of socket.io.min.js, a WebSocket JavaScript library, in their phishing pages, allowing the transmission of data to the actor’s server in a more streamlined fashion. This WebSocket integration corresponds to a mid-October 2023 update where Tycoon Group claimed that “link and attachment will be smooth.” In February 2024, Tycoon Group introduced a new “premium” service that bypasses the two-factor authentication of Google Gmail and Microsoft Office. This release also includes the “Latest Gmail Display” login page, and Tycoon Group claims it “works with Google Captcha.”

Most recently, Tycoon Group claimed that links support Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS) cookies, enabling subscribers to steal these cookies, specifically targeting authentication mechanisms that use ADFS.

The attack chain starts with a phishing email that uses a link to a reputable online mailer and marketing services, newsletters, or document-sharing services, such as DocuSign, Microsoft Cloud, OneDrive, Dropbox, Sharepoint, Google Drive, Microsoft Dynamics, Adobe Cloud, Flipsnack.com, Baidu.com, Paperless.io, Feedblitz.com, Marsello.com, RetailRocket.net, Padlet.com, and Doubleclick, as URL redirectors or to host a decoy document containing a link to the final phishing page.

Once a target clicks the link in the phishing email, they will be redirected to the landing page, composed of two primary components: a PHP script named index.php, which loads the secondary component, myscr(random digits).js. This second component’s function is to generate the HTML code for the phishing page.

“Index.php” Component

Trustwave identified two versions of index.php. Earlier versions feature HTML source code in non-obfuscated plain text. Later versions employ code obfuscation, using randomly generated variable names and a combination of Base64 encoding and XOR operations to hide the JavaScript link.

myscr JavaScript Component

This script also uses multiple obfuscation techniques to evade bot crawlers and antispam engines. One obfuscation technique involves using a very long array of characters represented as decimal integers. Each integer value undergoes conversion from decimal to character and is then concatenated to construct the HTML source code of the phishing page. In addition, the script uses an obfuscation technique known as an opaque predicate, inserting unnecessary code in the program flow to obscure the underlying logic of the script and makes reverse engineering harder.

Initially, the JavaScript component prefilters automated crawlers and humans using the Cloudflare Turnstile service to verify that a human is clicking the link. Tycoon Group’s PaaS subscribers can enable this feature in the admin panel by supplying Cloudflare keys associated with the subscriber’s account, which also adds visitor metrics for the phisher via the Cloudflare dashboard.

Upon successful verification, the JavaScript component loads a fake sign-in page based on the phishing theme configured by the subscriber, such as Microsoft 365. If a target inputs their credentials, the phishing page uses a distinctive method of exfiltrating the victim’s credentials. It utilizes the socket.io JavaScript WebSocket library to communicate with the command and control (C2) server, enabling the exfiltration of the data entered into the fake sign-in page. Usually, the phisher’s C2 server is hosted on the same domain as the phishing page.

Initial WebSocket request

wss://{THREAT ACTOR DOMAIN}/web6socket/socket.io/?type=User&customid={CUSTOMID}&EIO=4&transport=websocketInitially, the JavaScript on the phishing page transmits a message to the WebSocket server, sending information such as the maximum payload size, WebSocket ping interval and timeout, unique ID, and additional upgrade details.

The phisher’s WebSocket server then confirms receipt of this message by sending a received message that includes a randomly generated alphanumeric character. Then, the phishing page sends a WebSocket message to the server with four fields: send_to_browser, route, arguments, and getresponse.

“send_to_browser” specifies the action to be performed. “route” specifies if the data collected is an email (enteremail) or password (enterpassword). “arguments” is an array containing additional data or parameters for the specified route. For example, if the route specified is “enteremail,” it includes [“user email address”, “sid”, “browser type”, “IP”]. “getresponse” is a flag indicating whether a response from the browser is expected (1 for true, 0 for false). For instance, if the sender anticipates receiving a response, the value will be 1.

Once the message is received, the C2 server responds with a corresponding message with five fields: response_from_browser, message, bottomsection, backbutton, and description. During a test scenario, Trustwave entered an arbitrary email address, and the server replied with an error message indicating that the entered username did not match their target.

The “response_from_browser” field indicates that the data represents a response received from the browser. The “message” field specifies the nature of the response; in Trustwave’s test, it was “error,” indicating that the entered username did not match their target. The “bottomsection” field is an array containing objects representing clickable elements in the bottom section of the response. Each object may have properties such as a_text (anchor text), a_id (anchor ID), type (link type), and text (displayed text). The “backbutton” field is a binary flag indicating whether a back button should be shown (0 for no or 1 for yes). The “description” field is an object providing additional details or instructions, which may include properties such as a_text (anchor text), a_id (anchor ID), type (link type), and text (displayed text).

A high-level overview of the intrusion chain:

- Phishing email with a link or attachment.

- If the target clicks the link, the target is presented with Cloudflare’s Turnstile verification service.

- The service will display the phishing landing page if the target passes verification and establishes communication with the service’s server via WebSocket.

- If the target inputs their credentials, they are sent to the service’s server via WebSocket messages.

Risk & Impact Assessment

The Tycoon Group’s Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS) offering represents a considerable risk to organizations across various sectors due to its comprehensive features and ease of use, including customizable phishing campaigns, management of stolen credentials, and advanced features designed to bypass traditional security measures. The risk associated with Tycoon Group’s PaaS is primarily due to its ability to facilitate widespread phishing attacks with minimal effort from subscribers. This service’s ease of use, coupled with its subscription-based model, lowers the barrier to entry for cybercriminals. There is a reasonable likelihood that an organization will be impacted by Tycoon Group’s PaaS, especially considering the service’s enhancements, such as two-factor authentication bypassing capabilities and support for Active Directory Federation Services (ADFS) cookies. These features demonstrate the developer’s intention to overcome security defenses and its potential to enable unauthorized access to sensitive systems and data, making the platform more enticing to potential subscribers.

The impact of a cyberattack leveraging Tycoon Group’s Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS) could be severe for affected organizations. Financial repercussions may include direct losses from fraud, costs associated with response and remediation efforts, and potential fines for data breaches. Operational impacts could involve disruption to business processes and the theft of critical data, further compounded by the time and resources required for recovery. Additionally, the reputational damage from such an attack could significantly erode stakeholder confidence, leading to a loss of business and long-term harm to the organization’s brand. The theft or unauthorized access to sensitive information facilitated by Tycoon Group’s service could also expose the organization to espionage, targeted attacks, and a compromise of competitive advantages. Given these factors, the cumulative impact of an attack via Tycoon Group’s PaaS underscores the urgency for organizations to recognize and mitigate this threat through proactive security measures and awareness programs.

Source Material: Trustwave, Breakdown of Tycoon Phishing-as-a-Service System

Latest Additions to Data Leak Sites

Manufacturing – Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services – Finance and Insurance – Construction – Retail Trade – Information – Health Care and Social Assistance – Other Services – Education

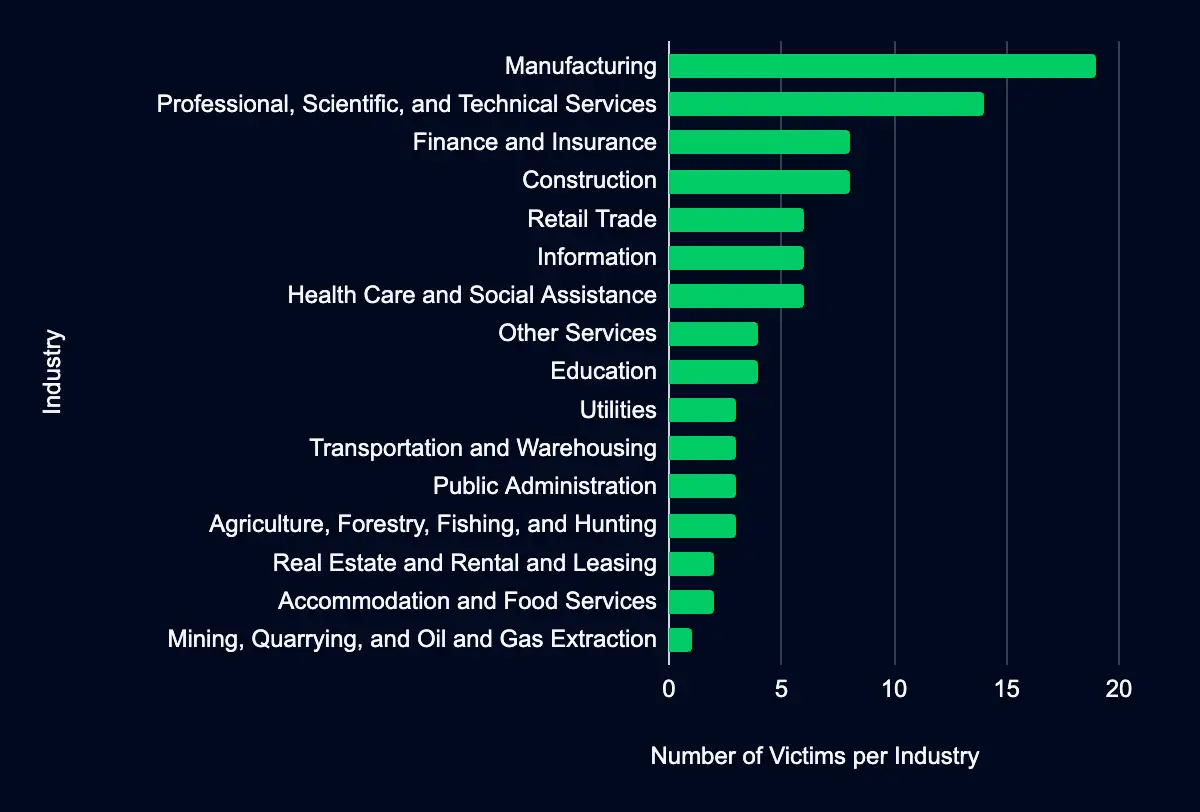

Recent data from data leak sites presents a compelling picture of ransomware and data extortion activities. 92 organizations have been listed as victims in the past week, with a marked concentration in the United States, with 53% of the total victims headquartered in this region. This geographic focus may indicate a higher targeting preference in this region due to its large economy, extensive digital infrastructure, valuable data, perceived willingness to pay ransoms, and cybersecurity challenges despite its involvement in global anti-ransomware activities.

Regarding industry targeting, the data reveals a diverse range of sectors being affected, with Manufacturing leading the list at 21%, followed by Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services (15%), Finance and Insurance and Construction (9% each), Health Care and Social Assistance, Retail Trade, and Information (7% each), and Other Services and Education (4%). This spread across diverse sectors suggests that the actors are not discriminating much regarding the industry, aiming for a wide range of targets. Another possibility is that many organizations fall under these sectors, providing a broad and diverse target base.

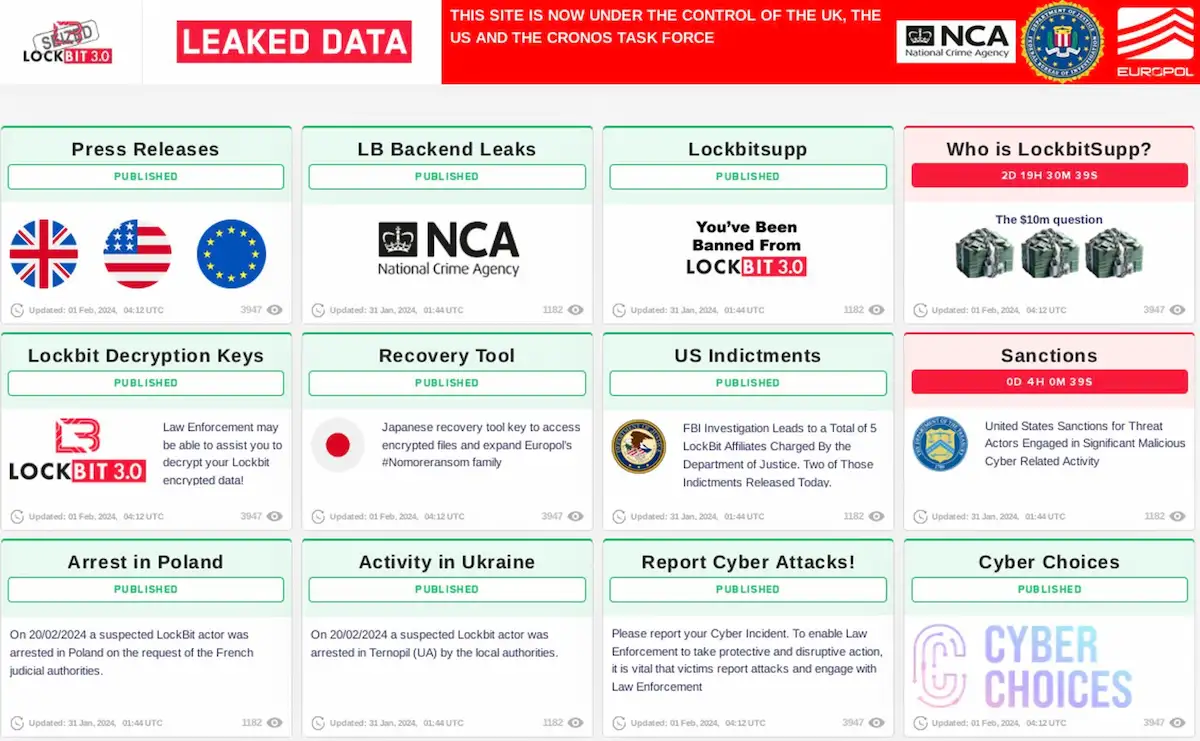

Lockbit, accounting for 41% of the victims listed in the dataset, predominantly targeted organizations in the United States but also had victims in the UK, UAE, Italy, France, and Argentina. While a notable number of their victims are in the United States (13), their large affiliate base likely accounts for their extensive geographical reach.

The spectrum of industries Lockbit’s victims operate in is equally varied, extending beyond Manufacturing and Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services to encompass sectors such as Finance and Insurance, Education, and Construction. This variety in targets underscores Lockbit’s affiliates’ opportunistic and versatile approach, possibly driven by the availability of opportunities across sectors. However, this week saw an important development.

On 19 February, an international law enforcement operation was made to take down Lockbit’s operations. This effort led to the arrest of three affiliates. This operation also seized Lockbit’s website. This international law enforcement operation involved the UK’s National Crime Agency, the FBI, Europol, and several international police agencies.

ALPHV, a group law enforcement temporarily stopped in 2023, accounting for 14% of the victims in the dataset, shows a more focused geographic targeting pattern but without clear sector preferences. ALPHV’s targets include organizations primarily headquartered in the United States, indicating that ALPHV is focused on this country. ALPHV victims predominantly operated in the utilities and manufacturing sectors. However, they also had at least one victim in various industries, such as Retail Trade, Finance and Insurance, and Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services.

This data suggests that while ALPHV is opportunistic, there is an inclination toward a specific region. For instance, their recent activities in the United States and their focus on utilities and manufacturing indicate a strategy that balances opportunism with selective targeting, possibly influenced by the perceived value of data or the ability to pay ransom. Their activities still underscore the unpredictable nature of ransomware groups, but with a nuanced approach that considers both opportunity and potential payoff.

The victims listed by Play, Black Basta, and Hunters International account for almost 25% of the total victims, offering valuable insights into the diversity of the ransomware threat landscape. Play Ransomware exhibits a focused but dispersed approach, with the vast majority of their victims headquartered in the United States across five industries such as Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, Manufacturing, and Transportation. This pattern suggests a focus on a specific geographic area but opportunistic in their sectoral preference, pointing towards a strategy that might prioritize opportunistic or easy targets over any particular industry or region.

Behind eight of the 92 victims listed in the dataset, Black Basta highlights the role of consistently active players in the ransomware arena. Black Basta exhibits a focused but dispersed approach, with most victims headquartered in the United States and the UK across six industries, such as Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services, Retail Trade, and Other Services. This pattern suggests a focus on a specific geographic area but opportunistic in their sectoral preference, pointing towards a strategy that might prioritize opportunistic or easy targets over any particular industry or region.

Behind six of the 92 victims listed in the dataset, Hunters International highlights the role of smaller but consistently active players in the ransomware arena. Hunters International exhibits a focused but dispersed approach, with most victims headquartered in the United States across six industries, such as Retail Trade, Other Services, and Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction. This pattern suggests a focus on a specific geographic area but opportunistic in their sectoral preference, pointing towards a strategy that might prioritize opportunistic or easy targets over any particular industry or region.

Our analysis strives to be comprehensive, utilizing the most current data available. However, it is crucial to acknowledge this data set’s inherent discrepancies. Despite our best efforts, the data set may include victims who are not listed on leak sites or were previously listed. Additionally, we may have omitted victims we could not verify. As the data set does not include information about the industry, we do our best to classify the victims based on the NAICS industry classification system. This manual effort may introduce other discrepancies, such as misclassifying the industry.

We also recognize that our data set does not represent the full scope of ransomware victims, as it only reflects those listed on leak sites, and groups do not list every victim they attacked on their sites. As such, while we believe our analysis provides valuable insights, it should be considered with an understanding of these potential discrepancies.

CISA Adds 2 CVEs to Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog

Microsoft Exchange Server CVE-2024-21410 – Cisco ASA and FTD CVE-2020-3259

Analysis

CVE-2024-21410 impacts Microsoft Exchange Server with a CVSS v3 score of 9.8; this vulnerability signifies a critical vulnerability, allowing a threat actor to escalate privileges. A threat actor could exploit this vulnerability to target an NTLM client such as Outlook with an NTLM credentials-leaking type vulnerability. The leaked credentials can then be relayed against the Exchange server to gain privileges as the victim client and to perform operations on the Exchange server on the victim’s behalf.

While specific exploitation details have not been disclosed, in 2023, Russia’s Fancy Bear (Forest Blizzard and APT28) took advantage of a similar flaw (tracked as CVE-2023-23397) in information-stealing attacks that targeted governments in the Middle East and several NATO nations. Microsoft has provided a resource dedicated to pass-the-hash attacks for organizations that want to learn more about the attack vector.

CVE-2020-3259 affects Cisco Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) Software and Cisco Firepower Threat Defense (FTD) Software with a CVSS v3 score of 7.5; this vulnerability signifies a high vulnerability, allowing a threat actor to disclose information. Exploiting this vulnerability could allow an unauthenticated, remote threat actor to retrieve memory contents on an affected device, which could expose confidential information.

The vulnerability is due to an issue when the software parses invalid URLs requested from the web services interface. The vulnerability was disclosed on 6 May 2020 and enables an unauthenticated remote threat actor to disclose sensitive memory contents from an affected device. This means that usernames and passwords can be retrieved from the memory in clear text. This vulnerability affects only specific AnyConnect and WebVPN configurations. For more information, see the Vulnerable Products section listed here.

For this vulnerability to be exploitable, the device with the vulnerable software must have Anyconnect SSL VPN enabled on the interface exposed to the threat actor. Akira Ransomware has been exploiting this vulnerability, as disclosed by Truesec in late January 2024. Their analysis of logs revealed a pattern in the threat actor activities related to the multiple accounts they had successfully compromised.

ATI recommends mitigative action occur according to the mitigation “Due Date” recommended by CISA.

| CVE ID | Vendor | Product | Description | CISA Due Date | Used in Ransomware Campaigns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2024-21410 | Microsoft | Exchange Server | Microsoft Exchange Server contains an unspecified vulnerability that allows for privilege escalation. | 3/7/2024 | Unknown |

| CVE-2020-3259 | Cisco | Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) and Firepower Threat Defense (FTD) | Cisco Adaptive Security Appliance (ASA) and Firepower Threat Defense (FTD) contain an information disclosure vulnerability. An attacker could retrieve memory contents on an affected device, which could lead to the disclosure of confidential information due to a buffer tracking issue when the software parses invalid URLs that are requested from the web services interface. This vulnerability affects only specific AnyConnect and WebVPN configurations. | 3/7/2024 | Known |

Let’s Secure Your Organization’s Future Together

At Deepwatch, we are committed to helping organizations like yours navigate the intricate world of cyber threats. Our cybersecurity solutions are designed to stay ahead of the curve, providing you with the proactive defenses needed to protect your organization from these threats.

Our team of cybersecurity professionals is ready to evaluate your systems, provide actionable insights, and implement robust security measures tailored to your needs.

Don’t wait for a cyber threat to disrupt your operations. Contact us today and take the first step towards a more secure future for your organization. Together, we can outsmart the threats and secure your networks.

What We Mean When We Say

Estimates of Likelihood

We use probabilistic language to reflect the Intel Team’s estimates of the likelihood of developments or events because analytical judgments are not certain. Terms like “probably,” “likely,” “very likely,” and “almost certainly” denote a higher than even chance. The terms “unlikely” and “remote” imply that an event has a lower than even chance of occurring; they do not imply that it will not. Terms like “might” reflect situations where we are unable to assess the likelihood, usually due to a lack of relevant information, which is sketchy or fragmented. Terms like “we can’t dismiss,” “we can’t rule out,” and “we can’t discount” refer to an unlikely, improbable, or distant event with significant consequences.

Confidence in Assessments

Our assessments and projections are based on data that varies in scope, quality, and source. As a result, we assign our assessments high, moderate, or low levels of confidence, as follows:

High confidence indicates that our decisions are based on reliable information and/or that the nature of the problem allows us to make a sound decision. However, a “high confidence” judgment is not a fact or a guarantee, and it still carries the risk of being incorrect.

Moderate confidence denotes that the information is credible and plausible, but not of high enough quality or sufficiently corroborated to warrant a higher level of assurance.

Low confidence indicates that the information’s credibility and/or plausibility are in doubt, that the information is too fragmented or poorly corroborated to make solid analytic inferences, or that we have serious concerns or problems with the sources.

Share